WHY THE METHANE DEAL COULD BE ONE OF THE MAJOR ACHIEVEMENTS OF COP26

Among the issues discussed at the COP26 negotiations there is methane, which is responsible for a major share of global warming and, as a pollutant, of more than a million deaths a year.

Back in mid-September 2021, the United States and the European Union agreed on a pact to reduce methane emissions, the Global Methane Pledge.

At COP26 in Glasgow, Biden and von der Leyen relaunched the methane agreement, and gained the endorsement of more than 100 countries, together accounting for about half of global methane emissions and for 70% of global GDP.

Approximately half of the 30 largest methane emitters have signed the pact, including Brazil, Nigeria and Canada. Missing from the list, however, are China, Russia and India, which alone are responsible for 30% of global methane emissions.

The pact calls for methane emissions to be reduced by at least 30% compared to 2020 levels by 2030.

According to a UNEP report, there are readily available and low-cost (or even cost-effective) measures that could cut anthropogenic methane emissions by more than 30% this decade and reduce global warming by 0.3°C by 2050. That may seem like a trivial amount, but it would make a huge difference in the impacts of the climate crisis.

Reducing methane emissions “ needs to be at a leader level of priority, […] because it has a similar importance to energy sector decarbonization in keeping 1,5°C within reach” said Rick Duke, Special Assistant on climate change in President Biden’s team, speaking at the COP26 side event “Driving Climate Action with Data – the Role of the International Methane Emissions Observatory”.

“This kind of diplomatic commitments matters to [government] stakeholders, to their agencies, to want they do on climate and with their economic priorities” he added.

The consequences of methane emissions on climate

In terms of anthropogenic emissions, methane is the second most abundant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide and is responsible for about 30% of the current warming compared to the pre-industrial period.

It is produced by landfills, agriculture, livestock farming (especially cattle), but especially by the oil and gas sector (30% of the total), where methane can escape along the entire value chain from extraction to use, including transport and storage.

Atmospheric levels of methane have increased by 150% over the past two centuries, with a significant spike during the past 20 years. For comparison, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has risen by about 50% over the same period. Studies conducted in the United States have shown that the increase of methane in the atmosphere has followed a curve parallel to the growth of “fracking” processes (hydraulic fracturing, an invasive oil extraction technique that has gained considerable momentum in the U.S. in recent years).

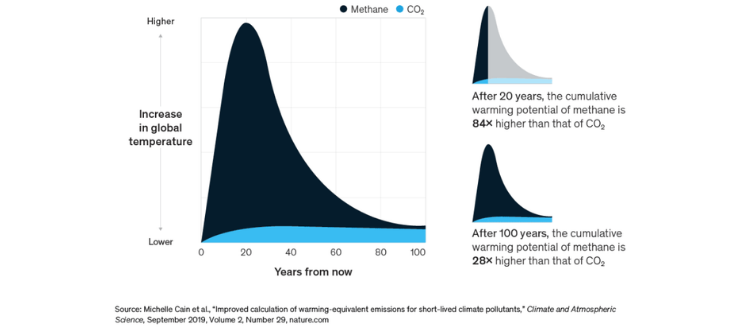

How can the emission of methane be so effective in determining global warming, when this gas is released in quantities far smaller than CO2? Although it stays in the atmosphere less than CO2, having an average lifetime of about 12 years, methane has a total heat-trapping capacity (technically GWP, global warming potential) of 84 times that of CO2 in a 20 year period, 28 times in 100 years.

Credits: McKinsey

The consequences of methane emissions on health

In addition to being an extremely potent greenhouse gas, methane is also harmful to health. Its emission is often accompanied by hazardous substances, such as benzene, and it is a precursor to tropospheric ozone (not to be confused with the stratosphere ozone -at an altitude of more than 10 km above sea level – that protects us from solar UV).

Exposure to these pollutants has been linked to serious illnesses, including asthma and cancer, with an estimated value of more than one million premature deaths per year due to the methane emissions.

Can methane emissions be reduced?

The United States and the European Union are the two largest consumers of fossil gas, which is composed almost entirely of methane. This means that any efforts they make to limit leakage at the national level or within gas supply chains could have a significant knock-on effect. The “Global methane pledge” ensures international political support for EU and US measures in this regard.

In the USA, the largest source of methane emissions is the oil and gas industry, which alone emits more methane than all the greenhouse gases generated by 164 countries combined.

Just a few days ago, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a package of new standards and regulations that would reduce “methane emissions from the sources considered in the proposal by 74 percent compared to 2005” by 2030. All this would be possible with only small variations – “pennies per barrel of oil or thousand cubic feet of gas” – in the price of gas and oil.

According to the International Energy Agency, in fact, ” around 40% of current methane emissions could be avoided at no net cost “(IEA, Methane Tracker 2020).

In essence, “methane emissions are avoidable, the solutions are proven and even profitable in many cases. And the benefits in terms of avoided near-term warming are huge (Faith Birol, IEA).

“Profitable” because these emissions also represent a huge waste of natural resources: every year we waste an amount of methane equal to about three-quarters of Russia’s total annual production. This methane could instead be sold, paying back the “anti-waste” investments.

How methane emissions can be tracked?

The extent to which such leaks occur is only approximately known, due to the difficulty of measuring them: ” The lack of verified data has made hard to carry out targeted actions at scale and at speed” said Inger Andersen, Executive Director of UNEP, during the Side Event.

For example, currently in Italy it is up to the oil companies to perform the measurements and send them to ISPRA to be included in the national greenhouse gas inventory.

Methane can in fact be detected in-situ by an infrared camera, or through measurements from aircraft. In recent years, thanks to their ability in providing daily data on the entire planet, satellite images have finally provided new solutions: in this way it has been possible to identify super-emission events of in Russia, Iran, Turkmenistan and Australia, countries that have not signed the agreement.

“Super emitters are the ‘low hanging fruit’ of detection and mitigation” (Ilse Aben, senior scientist at SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research).

Is methane the transition fuel?

It’s worth considering the much-ballyhooed possible role of methane in the energy transition. Well, a study by the Environmental Defense Fund showed that methane losses of only 2.7% of transported natural gas are likely to compensate the short-term climate benefits due to the use of natural gas instead of coal. Recent research, unfortunately, shows that local losses are not far from that percentage, if not greater.

Fossil gas, in short, must stay firmly underground.

Elisa Terenghi, Italian Climate Network Volunteer for COP26