GENDER EQUALITY AND TECHNOLOGY AT THE COMMISSION ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN

The Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), the intergovernmental body of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) dedicated to the promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women, dedicated its sixty-seventh session this year to the theme Women and Technology (“Innovation and Technological Change and Education in the Digital Age to Achieve Gender Equality and Empowerment of All Women and Girls”).

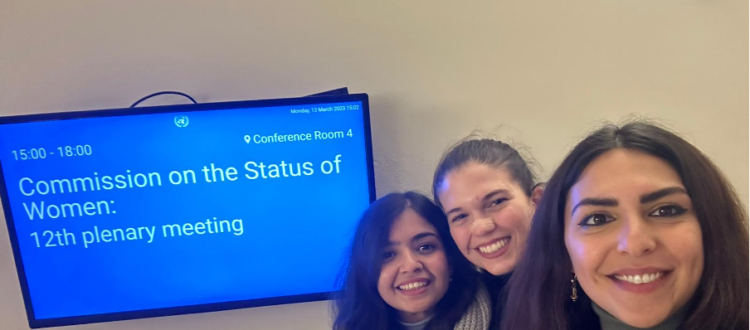

ICN followed the event through three young women – Alma Rondanini, Pegah Moshir Pour, and Aarushi Khanna – from the National Gender Youth Activist, a group of 300 activists who work with UN Women to ensure youth participation at all levels in supporting gender equality. We then interviewed these young activists to find the results.

One of the first questions we asked them was about the structure of the CSW itself and whether it fulfilled the objectives of its mandate in substance. In this sense, the body hinges on the concepts of inclusiveness and intersectionality, which means that by its very nature, it should be a space for dialogue that can accommodate everyone. However, according to Aarushi, there are still barriers to entry that make the Commission inaccessible to certain social groups and minorities. This does not mean that progress in ensuring widespread representation has not been made, but unfortunately, some obstacles remain to be overcome.

The first problem lies in the fact that to be received at the glass palace where the CSW meets, it is necessary to have received an accreditation badge from the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), which is not an easy process, Alma points out. In addition, the costs and logistical/bureaucratic barriers are unsustainable for young activists and some communities in the Global South, points out Aarushi, who notes that hybrid participation (in-person and online) could have been opted for. Finally, the question of the visibility of these events, which seem to be known only to a small circle of activists, remains open. In this sense, Pegah believes that they should be made more mainstream to ensure greater democratisation and inclusion.

Another aspect that intrigued us concerns the degree of technicality of the topic under discussion, i.e. the intersection between gender and technology, which requires specific expertise in both fields. From this point of view, both Aarushi and Alma inform us that the delegates were not always adequately prepared on the topics they were called upon to negotiate. On the contrary, the civil society representatives had gone to great lengths to arrive prepared for the CSW. This was done, for example, through consultation processes with various social groups and minorities to gather ideas and suggestions to share with the delegates or through the recent revitalisation of the Youth Caucus as a platform for dialogue.

As Alma and Aarushi also point out, this gap is primarily due to the precise political choices of the governments selecting their delegates. Also influencing the outcomes of the negotiations are the power dynamics within the CSW. Indeed, it must be said that some delegates have more influence than others under their lobbying skills. This situation is further accentuated by the fact that, as mentioned earlier, certain social groups or communities are excluded from the negotiations. In this sense, the demands of the Vatican seem to carry proportionally more weight than the more progressive proposals of some countries in the Global South.

Finally, the general international context, starting with the war in Ukraine and the disagreements between America and some states, also played an important role. Indeed, the Iranian delegate was not present as he was not invited to attend CSW67. Moreover, there are groups of states that have a greater interest than others in obtaining as many international commitments as possible. The countries of the Global South are in the first group, while the Western countries present themselves as more conservative. These dynamics seem in fact to replicate those of the climate negotiations.

So what are the final observations on CSW67? In this regard, our activists report that the final text of CSW67 turned out to be less promising in content than expected. In fact, they point out to us that precisely for the reasons stated above, the conversations around the topic of gender and technology did not go too far into the root of the problems they wanted to solve. In the same way, there was no granular discussion of issues such as digital security (safeguarding) or the role of ‘users’ of digital media. There is, therefore, still a long way to go to achieve substantial equality in this area, and all that remains is to keep fighting for more and more results.

Article by Erika Moranduzzo and Camilla Pollera, ICN Volunteers and Climate and Rights Section Co-Coordinators