THE GLOBAL STOCKTACKE DRAFT OF 8 DECEMBER, POINT BY POINT

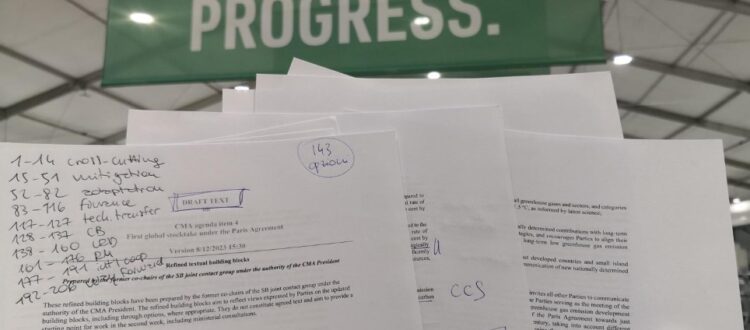

In the twenty-seven pages of the Global Stocktake text published on the UNFCCC website on 8 December at 3.30pm (Dubai time), much of the future of the Paris Climate Agreement begins to take shape. The text is still tremendously messy and full of negotiating options to unravel (as many as 147 counting sub-options). A text built on “building blocks”, as the facilitators explain, which nevertheless already outlines very clearly the general direction of the negotiations and the main critical points.

In this article we will examine one by one the main issues of friction between the delegations, namely almost all with negotiating options still open, going beyond the media debate solely on the phase-out and trying to provide Italian Climate Network readers with a complete picture. We point out that the numbering of the paragraphs will certainly undergo changes in the drafts of the coming days, given the inevitable “cut and sew” that this text will go through in the various negotiation iterations.

Preamble

In the preamble there is no mention of 1.5°C

In the preamble, the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities” takes the centre stage, being included in the second paragraph. The first, on the other hand, recalls the general objectives of the Agreement, but without explicitly mentioning them, thus lacking in this part a clear reference to keeping global temperatures within +1.5°C at the end of the century. This omitted citation is recovered in the following pages, particularly in the section on Mitigation (paragraphs 15-51), but may be relevant to a text that will, in fact, point the way post-2023 for the Paris Agreement.

Important mention of human rights and of the rights of indigenous people

Prominent in the sixth paragraph of the preamble is a strong reference to rights. It is said, in fact, that countries should respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to a sustainable, clean and healthy environment, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children and persons with disabilities, also taking into account gender equality and intergenerational equity. The organisations fighting for the rights of persons with disabilities are satisfied with the draft, less so those working on human rights, who see in the concept of mere “respect” a lower level of protection, compared to terms such as “protection” that are considered more active. It is probable, in any case, that this paragraph will be heavily modified or moved, given the variety of focuses and the current positioning at the “higher levels” of the text. It should be noted that as of now no further mention of human rights appears in the following paragraphs. Finally, the concept of “climate justice” is also mentioned, in a sub-paragraph which, again, will certainly be modified and/or moved in the final text – if not eliminated altogether.

Background and cross-cutting considerations (paragraphs 1-14)

“We’re not there yet”

Paragraph 2 points out that “despite progress” in recent years, “the Parties are still collectively not on track towards achieving the overall objective of the Paris Agreement and its long-term goals”. Paragraph 5 says, moreover, that the countries “note with alarm” that “human activities, mainly through the emission of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally (author’s emphasis) caused global warming of about 1.1°C”, a formulation that is by no means trivial given the resistance of many countries to using such strong scientific language and, if you will, given the recent statements on the subject by COP President Al Jaber himself.

International climate justice, different points of view (or let’s not talk about it at all)

Paragraph 7, which in the intentions of those who proposed its inclusion in the text should talk about the issue of climate justice in terms of a fair redistribution of obligations between countries, offers no less than 5 negotiating options. The first four recall concepts that have always been dear to developing countries. Option 1 sees international climate justice as a possible drive towards better and more coordinated action towards the long-term Paris goals. Option 2 emphasises the complexity of the current global situation, reaffirming the importance of historical responsibilities and respect for human rights. Option 3 complements option 2 with a more specific focus on human rights, poverty eradication and national contexts. Option 4, finally, refers more dryly and succinctly to the CBDR-RC principle (common but differentiated responsibilities), offering a text that is perhaps sharper than the previous ones, but less ambitious. Option 5 is a no-option, i.e. it proposes not to talk about the issue.

Historical responsibilities and conditionality of Southern commitments: a very “strong” text

Paragraph 8, with two negotiating options, offers an even stronger lunge on the issue of historical responsibilities, certainly according to texts proposed by countries of the Global South. It reads, in fact, that the COP “recognises that equitable mitigation actions are driven by historical responsibilities” and that “developed countries should lead” the process. Furthermore, it is emphasised that “the degree to which developing countries’ commitments are actually implemented will depend on the objective implementation of developed countries’ commitments” in terms of mobilising climate finance and technology transfer. If this language already seems very strong, the paragraph goes on to emphasise that “economic and social development and poverty eradication are first and crucial priorities of developing countries”, underlining that there will be no climate action at the global level without real financial involvement of rich countries in support of the Global South. A very strong and decisive formulation, on which countries could debate for a long time. The second option is a no-option.

The elephant in the room: the CBAM (which many do not like and is being attacked through the COP)

Paragraph 13 is the first to mention, without citing it, the new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) envisaged by the European Green Deal, which proposes the establishment (on an experimental basis on some sectors as early as this year) of a new taxation for goods arriving in the European Union and coming from countries and production systems that do not apply substantial reductions in climate-changing emissions on those productions. The text takes Article 3.5 of the 1992 UNFCCC as a starting point, recalling that global climate action will thrive in a world of open and accessible markets, and emphasising that “unilateral climate policies […] shall not constitute arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination or disguised restrictions on international trade”. Again, a very strong formulation, which is then repeated in subsequent paragraphs throughout the body of the text, underlining that the new policy on “green” imports imposed by the European Union is already triggering tensions in many partner countries. Countries that are attempting to bring the political clash into the COP halls, hoping to exploit the numerically favourable context (for them) in the UN fora to fight an otherwise complex battle in the world of bilateral trade interactions.

Mitigation (paragraphs 15-51)

The finger pointing (at whom?)

Paragraph 23 offers three negotiating options, one of which is a no-option. It talks about reducing emissions and reducing the time space to do so, according to various data and time references, all with reference to the latest IPCC and UNFCCC reports. It is surprising, however, that at the end of option 1, the finger is pointed, without naming them, at two developed countries that, according to the latest five-year emissions reports, have failed to meet their international commitments. This is quite unusual for a negotiating text in the UN, where, by practice, the finger should never be pointed. This paragraph will almost certainly be amended or deleted in the final part.

Peak emissions in 2025 (or not?)

Paragraph 25 offers three options, one of which is a no-option. Option 1, in two sub-options, clearly states the need to reach the global climate emissions peak by 2025, also asking countries to communicate the expected peak date of their emission systems. Option 2, on the other hand, makes a generic reference to the need to stay within the boundaries of the emission budgets indicated by the reports, with attention to the fair distribution (in terms of CBDR) of this budget among all countries.

Paragraph 27, then, offers three options, one of which is a no-option: it refers to the conditionality of developing countries’ NDCs, with references to projected emissions growth in percentage terms (option 1) or the residual possibility of reaching global peak emissions by 2030 (option 2).

CCS – phase out – Unabated – Subsidies: the key paragraph of this COP

Paragraph 36 of today’s draft is probably the most important one in the entire text. It presents two textual macro-options, of which the second is a no-option while the first offers a detailed outline of the political direction to be taken in the coming years in terms of mitigation, with no less than 6 sub-paragraphs divided into 16 sub-options. But let us go by points.

- Renewable capacity x3, alone?

Under (a) we now have two options and a no-option which, with different formulations, both offer the COP’s decision to triple renewable energy generation capacity globally by 2030. The difference lies in the fact that the second option says that this “x3” cannot be achieved without the concomitant reduction, to the point of disappearance, of fossil-based energy production, a non-trivial clarification on a commitment already considered as made.

- Carbon capture and storage: should we talk about it here or not?

Under (b) there is a mention of the fact that countries will have to invest in carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies to stay within the targets; the other option is not to talk about it at all, a no-option.

- Phase-out: it is included in all options – and it is big news

Under (c), delegates have left the wording “phase-out” in as many as four out of four options (the fifth is a no-option), a political fact perhaps unthinkable just a few days ago – but the COP is still a long way off. It says, in fact, that countries will have to pursue “a phase-out from fossil fuels according to the best available science” (option 1); that they will also have to do so in line with the IPCC special report on 1.5°C and the Paris Agreement (option 2); that they will have to pursue “an exit from non-CCS-compensated fossil fuels recognising the need to peak in their consumption by 2030, emphasising the importance for the energy sector to be predominantly fossil fuel free well before 2050” (option 3); that they will have to “exit from non-CCS-compensated fossil fuels” and reach net zero in energy systems “by or within” 2050 (option 4). Option 5, incorrectly referred to as 4, is a no-option.

- Rapid exit from unabated coal

Under (d), the only textual option proposes a “rapid exit” from unabated coal-fired power generation by 2030, together with the immediate cessation of any new coal-fired power generation licensing practices.

- Fossil fuel subsidies promoting social welfare (…?)

Undoubtedly curious is the current wording under (e), which promotes an exit from fossil subsidies that do not entail concrete and positive commitments on energy poverty and just transition. A paragraph that certainly needs to be revised and, above all, better explained.

The paragraph closes, as mentioned, with option 2 being a no-option, thus with the real possibility that of all these issues we will end up, at the end of the negotiations, not talking at all. A politically improbable prospect.

“Transition fuels” and methane: two brief hints

Paragraphs 38 and 39 offer two meagre textual options, we might say two hints, on the “important role of transitional fuels in facilitating the energy transition” and the need to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030, with mention of other greenhouse gases. Both paragraphs have a no-option, they could therefore be modified or deleted.

An attempted “putsch” on net zero to 2040

Paragraph 49 addresses, with two text options and no no-options, the review of the long-term strategies of countries under Article 4.19 of the Paris Agreement, inviting them to submit their updated strategies by the next COP. Significant and important is the attempted coup by some countries that in option 2 included a request for developed countries to include in their strategies “time references for achieving net zero by 2040 and negative emissions as soon as possible”. A strong and ambitious wording, which may not survive the coming days of negotiations.

Adaptation (paragraphs 52-82)

A new IPCC special report on adaptation?

Paragraph 77, in the first of the two options, calls on the IPCC to prepare a new special report, this time on adaptation, which could include metrics and indicators to support the preparation of the next Global Stocktake in 2028. The second option reiterates the importance of science’s commitment to the topic but does not mention the idea of a new special report.

Confusion over doubling of finance for adaptation

Paragraph 82 is supposed to address, in the intentions of the delegates, the doubling of finance for adaptation and the need for a roadmap to reach the goal, but then it gets lost in three options (the last one is a no-option) written in a rushed and incomplete manner, with typos and residual “xx”. Developments in the coming days are certain, barring the complete deletion of the paragraph.

Finance (paragraphs 83-116)

100 billion per year: hawks and doves

On the long-standing issue of the years-long failure to meet the target (now dating back to 2009) of mobilising globally at least $100 billion per year in climate finance, the COP28 delegates seem to be settled on two positions. In paragraph 87 we find three options: option 1 “welcomes” – we could translate as “greets” – the international efforts of recent years to get closer to the target, in the context of “sensible” mitigation actions (?); option 2 on the other hand “notes with deep concern” the distance between the target and reality, again in the context of “sensible” mitigation actions. Option 3 sees the first “placeholder” in this text, i.e. a space deliberately left blank to insert results from other negotiating strands, in this case the outcomes of the work on long-term finance. Hawks versus doves, with an opening to… talk about something else.

Climate finance: what does it mean? (disbursements versus guarantees)

The four text options in paragraph 90 highlight differences in views on what should be understood by “quality climate finance”. The four options, in fact, differ in their vision. Option 1 emphasises the central role of climate finance in the form of disbursements, which are necessary to attack the problem of the lack of resources where loans still dominate today, weakening the most fragile financial systems. Option 2 emphasises the same concept but in less detail. Option 3 mentions disbursements as possible solutions alongside loans. Option 4 speaks of “stimulus packages” without specifying whether this means disbursements or something else, in any case provided by developed countries, but designed and managed by developing countries. Different nuances in the first three options (from the most to the least ambitious for the countries of the Global South) and a fourth option that seems to refer, perhaps, to another theme or to a paragraph later deleted and merged with the 90. The theme of defining climate finance also returns in paragraph 92 below.

Climate finance: alignment with the Paris Agreement or…?

Paragraph 93 is supposed to deal with the issue of the necessary alignment of climate finance flows with the goals of the Paris Agreement, as set out in option 1, but then gets lost in considerations of the role of non-UNFCCC actors in option 2 and closes with a no-option 3. A confusing and incomplete paragraph, which will surely be twisted, rewritten or merged into others in the coming days.

100 billion a year: target achieved or not?

As messy as this negotiating draft is, the topic of $100 billion a year dealt with in paragraph 87 comes back in paragraph 97 with two distinctly discordant options: in option 1 the delegates “recognise the distance that remains to reach the target of $100 billion a year”, in option 2 they “welcome the recent data in the OECD report, including the prediction that the target has been reached in 2022”. There is confusion.

An ad hoc paragraph on the importance of the private sector… or not?

The only non-no-option in paragraph 109 emphasises the “cardinal” importance of the private sector in climate finance, and the delegates set themselves the goal of strengthening the rules governing its participation in the effort, making the conditions for participation as easy as possible in national contexts. A paragraph that, on the one hand, seems to refer back to the report against greenwashing in private climate finance presented by Antonio Guterres last year, on the other hand, seems to end up here in the text almost by accident, given its location and unusual brevity. It could end up being deleted or merged with something else.

A new work programme and an exit from fossil fuel subsidies (maybe)

Paragraph 113 sees two options, one of which is a no-option. It proposes the launch of a new work programme on the implementation of Article 2.1.c of the Paris Agreement, which asks countries to make financial flows compatible and aligned with climate goals. The aim of the new work programme should be to collect good practices and “send signals” to politics, catalysing actions and investments on mitigation and adaptation as well as identifying elements to avoid greenwashing as best as possible. This possible work programme would be an extra, something new outside the Paris Agreement, and it is not a foregone conclusion that the idea will survive the week’s negotiations: new initiatives, new work programmes are always being exchanged in the final hours of negotiations, between those who push to launch them and those who do not. Paragraph 115 below also calls for countries to reduce (not eliminate) financial flows not consistent with climate action, e.g. “by exiting fossil fuel subsidies and establishing a price on carbon”: strong and perhaps unexpected wording in this seemingly anonymous paragraph on bad finance. What, of this paragraph 115, will survive the final hours of quid pro quo remains to be seen.

Technology transfer (paragraphs 117-127)

A new $2.5 billion technology implementation programme

Paragraph 126 of the draft sees the proposal, in a dry and binary “yes-no” to two options, one of which is a no-option, to establish a new “Technology implementation programme”, with an initial budget of $2.5 billion to be renewed in line with any future Global Stocktake. Thus – if we interpret this correctly – with five-year allocations of the indicated figure, with a first operational period 2023-2028, a second period 2028-2033 and so on, to support the drafting of each new round of NDCs, but also the review of all national plans on adaptation, mitigation and any transparency reports under the UNFCCC. A draft decision on the new schedule is called for by the end of the next COP in 2024. The second option is a no-option, thus with the possibility that the idea of the new programme will be removed from the text altogether.

Capacity building (paragraphs 128-137)

A new fund for capacity building?

Paragraph 137 envisages the creation of a new fund to support capacity building actions, i.e. to support developing countries in their implementation of NDCs (option 1), or simply to support initiatives already undertaken in this regard by the Green Climate Fund (option 2). Or nothing at all, as per option 3. This new fund is another idea that might easily not survive the negotiations. But someone tried and the facilitators could not fail to account for this in the draft.

Loss and damage (paragraphs 138-160)

Who pays? Europe tries to involve China

If this part of the draft on loss and damage seems substantially solid compared to the rest, paragraph 155 stands out. In the only textual wording (thus, in theory, not challenged by alternative proposals or possible deletions) it says that the COP, in addition to recalling the crucial role of rich countries in contributing to the new Loss and Damage Fund, “encourages other Parties to provide, or continue to provide support, on a voluntary basis, for activities affecting loss and damage” in line with other COP decisions. The position of Europe and of many developed countries is strongly felt in this wording, which aims to engage the new big emitters (China and, indirectly, the Gulf oil countries) to contribute financially on loss and damage, given their recent role as historical co-respondents. The paragraph is the only one in the entire text with a footnote, probably inserted under Chinese or Arab pressure, saying that this paragraph is not intended to prejudice any future agreement on individual countries’ contributions. A “band-aid” on a fairly straightforward text, which if kept in this form could provide a formal basis for those who, in negotiations over the next few years, might want to hold Beijing to account for its emissions not “offset” by reparations. Perhaps one of the most politically relevant paragraphs of the entire text – footnote included.

Towards an annual (!) UNFCCC report on the Loss and Damage Gap

In paragraph 160, in the only non-no-option, countries ask the UNFCCC Secretariat to develop an annual report on the loss and damage gap, with the aim of providing useful working elements for subsequent Global Stocktakes, by establishing the topic of loss and damage as a permanent item on the agenda of each future COP. It will be interesting to see whether the idea of the gap report will survive the second week’s negotiations. It is odd that an annual report is requested to provide information to a five-year review process, probably a drop point acceptable to all would be to align the request to the (five-year) Global Stocktake cycle.

Impacts of climate action (paragraphs 161-176)

One confusing text, two different worldviews – and another attack on the CBAM

In the facilitators’ idea, in paragraphs 161 to 176 the visions and demands of countries regarding the impacts (positive and negative) of mitigation and adaptation actions on local communities were collected. Unfortunately, to date, this part of the draft is still quite confusing, with repeated themes and messy paragraphs. Of particular note is paragraph 163, in which two different textual options link the impacts of mitigation and adaptation measures to the right to development of the poorest countries: such a right (following the text) could be compromised by the need to implement the energy and ecological transition, while the subsequent paragraph 167 instead attempts to emphasise the positive effects of the transition in terms of employment and economic growth resulting from proactively maintaining a trajectory compatible with the Paris Agreement. Two different worldviews and urgency, with the first part of the text probably proposed and suggested by countries particularly hostile to more ambitious policies. There is no lack – in paragraph 175, option 1, point (b) – of a further reference to the negativity of unilateral, bilateral and multilateral “coercive” actions with respect to international trade (with reference, of course, to the CBAM of the European Green Deal), a formulation already seen above in paragraph 13.

International cooperation (paragraphs 177-191)

Forward with the price on carbon

Paragraph 188, with one non-no-option, says that the COP “notes the current initiatives to establish a price on carbon and encourages Parties to adopt, implement and improve such measures to align with the long-term vision and objective of the Paris Agreement”. The inclusion of this wording in the section of the text on international cooperation clearly refers to the ongoing negotiations on the controversial and complex Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, and it is clear that some countries are, in this sense, trying to push the process forward towards greater ambition (we are thinking in this sense of the European Union, but not only). It is possible that the paragraph will be amended, less probable that it gets deleted, given the non-mandatory wording of the text.

Another attack on the CBAM (the third)

The protagonists of paragraph 189 are again the “unilateral” measures “imposed by some countries” that include, for example, “green barriers” (to incoming goods), “discriminatory legislation, blockades and plurilateral impediments” (?) that “are not aligned with the Paris Agreement, in particular in terms of common but differentiated justice and responsibilities and respective capabilities, as well as with WTO rules”. In short, this option 1 of paragraph 189 does not hold back, for the third time in the text, regarding measures such as the European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism that has just come into force on an experimental basis as per the roadmap of the European Green Deal. Option 2 is the deletion of the paragraph. With this third mention the CBAM becomes to all intents and purposes the most debated topic in the draft to date – at least at the level of mentions in the text, certainly not indicative in absolute terms of political weight, but nevertheless relevant for the purposes of this analysis.

Looking ahead (paragraphs 192-206)

‘Next’, ‘forthcoming’, ‘to 2025’: when the new NDCs?

Paragraph 192 deals with the timing of the drafting of new national plans under the Paris Agreement, the NDCs. We specify that, according to the Agreement, NDCs follow at least five-year (improvement) review cycles starting in 2020 (the first year of temporal operation of the Agreement) and that they must be updated with policies and measures for the following five years or decade. This means that new, more ambitious NDCs at 2025, covering the years 2030 to 2035 or 2040, should emerge from the findings of the 2023 Global Stocktake. Paragraph 192 deals with the subject in terms typical of the Paris Agreements, but the devil is in the detail: the text – chaotic and with options not enumerated except by ordinal numbers in para-Latin as if they were all part of the same text – says that countries will have to prepare the “next” NDCs, then “every five years”, then “next”, then “within at least 9 to 12 months before COP30”, then again “in 2025”. A text, in short, very chaotic, but important in order to understand, in what will be the final and definitive text, the actual ambition of the countries with respect to an acceleration in the revision that it’s still possible – after all, in 2021 it had already been written into the Glasgow Climate Pact, with the deadline of 2022 then becoming impossible.

Women, youth, human rights

Almost as if to complete an internal circularity in the text, or perhaps because no better place could be found to insert it, paragraph 198 seems to echo the preamble in emphasising the importance for countries to work (“is encouraged”) on gender-sensitive climate policies, in full “respect” (again, not protection) of human rights, supporting the active participation of youth and children. A short paragraph, but perhaps a little too “copy and paste”, apparently surviving the first cuts at the request of some countries, but with an uncertain future.

Is CBAM evil? (fourth mention)

In paragraph 199 ther3 is a fourth non-explicit mention of the negative effects of measures such as the European CBAM; it repeats almost exactly the text of the previous paragraphs on the subject. Fourth mention and first place on the podium for the most mentioned and debated topic in today’s draft.

A new IPCC special report on transition costs?

Paragraph 201 invites, in option 1, the IPCC to produce a new special report, this time on the costs of the ecological transition in scenarios that contain global warming within the Paris targets. Option 2 reduces the effort to updating models and trajectories. Option 3 simply asks for the development of a simplified and understandable methodology for countries to communicate their historical emissions (therefore perhaps going a little off topic, probably again a little too quick “copy and paste”). It will be interesting to see if the demand for option 1 will make the cut in the second week. From what can be understood from the text to date, it seems more like a fall-back option, proposed by unambitious countries. We also remember that already in paragraph 77 the IPCC was asked for a new special report, but on adaptation.

An annual UN report on progress after the stocktake?

In paragraph 203, letter (a), option 1, the UNFCCC Secretariat is asked to prepare annual reports on the progress of climate policies starting from COP29, underlining the progress made and the level of implementation of the decisions linked to the first Global Stocktake of 2023, therefore of this same text that we are commenting on. Option 2 is a no-option. This could undoubtedly be one of the most interesting innovations of this negotiation. It remains to be understood, if it survives the second week, with what resources and with which experts (in short, who pays?) the Secretariat could start such a virtuous but also such onerous process in technical, scientific, and reporting terms. Unusually, the following letter (b) waters down the idea, proposing only “data explorers” on emissions in option 1, and then moving on to a no-option. In short, new annual reports today have a one in four chance of survival. But the negotiation is long.

A new GST Forum?

Option 1 of paragraph 204 provides for the launch of a new tool for formal discussion between the Parties on the outcomes of the Global Stocktake and in view of the next ones: it is called “GST Forum”, and it should be where discussions and workshops on how to best prepare the upcoming NDCs are organized. Additionally, the same option envisages the establishment of a permanent point on the agenda of future COPs to collectively evaluate how Global Stocktake is helping countries in drafting their new NDCs. The subsequent options 2 and 3 water down the idea, respectively proposing a milder roadmap (option 2) and underlining the importance of collective work by countries (option 3).

Towards new NDCs: more events, or a single one with Guterres in 2025?

Paragraph 205 will need to be monitored carefully as it may reveal the overall ambition of this COP with respect to the central process of the Paris Agreement, the review of the NDCs. In fact, in option 1, it is said that the COP “invites the Presidents of COP28, COP29 and COP30 to build on the political momentum of the Global Stocktake by convening high-level political events on the preparation and communication of the (new) NDCs, including a focus on their alignment” with the goal of 1.5°C. Option 2, however, moves the issue forward in time, suggesting that countries “present their revised NDCs at a special event under the auspices of the UN Secretary-General to be held in 2025”. It is interesting to note that on this issue, we repeat very centrally, there is no consensus, to the point that there is still a no-option 3.

Jacopo Bencini, Policy Advisor, European and Multilateral Climate Policies Italian Climate Network