CLIMATE AND HUMAN RIGHTS: THE COMMITMENT OF CIVIL SOCIETY BEYOND THE UNFCCC

INTERSECTIONALITY AS A KEY TO MAKE CLIMATE ACTION CROSS-CUTTING

The actions that will be taken in the coming decades to counter the causes and impacts of climate change will increasingly be at the heart of every aspect of the administration of every society on the planet. The Conferences of the Parties (COPs) of the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in particular seem to be increasingly influencing the agenda of other UN bodies and entities, making it clear that no societal challenge can any longer be addressed without taking climate into account. This is not new to that part of civil society working on climate, environment and human rights issues, but for a great many specialists and policy makers, this new dimension has only taken shape in recent years.

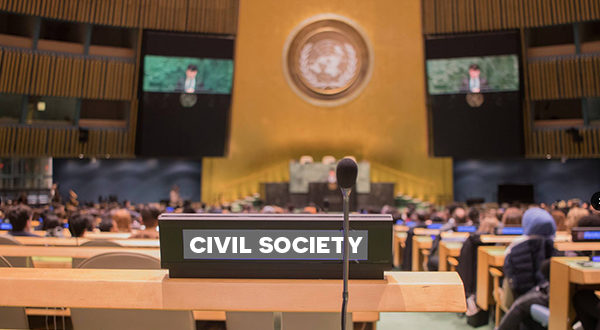

Many members of civil society from all over the world are active within the UN climate negotiations and work for the integration of human rights principles within the negotiation texts to ensure that in the name of reducing emissions, other ecosystems are not destroyed and/or people’s rights violated. In many cases, the same organizations active within the COPs are engaged in other UN spaces traditionally dedicated to other issues, pushing to work in an increasingly intersectional manner, that is considering the complex links between areas previously considered independent of each other.

CLIMATE WITHIN THE COUNCIL FOR ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RIGHTS

Civil society, in an effort to accelerate the integration of areas interconnected in reality but conventionally divided in the institutional machinery of the United Nations, also operates within the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). The Council is one of the main organs of the United Nations and has advisory and coordinating functions for the UN’s work in economic and social cooperation and in the promotion and protection of human rights. For years, civil society has pushed for the consequences of climate change on the environment and the rights of people to be considered as an integral part of every aspect of the Council’s work. One of the results of this relentless political pressure was seen in 2015, when with the end of the “Millennium Development Goals” (MDGs), ECOSOC sought to remedy the shortcomings of the program (which at the time covered only eight action areas) by expanding it. The program, renamed the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), not only includes a climate- and environment-related concept in its name (sustainability), but also has climate action (SDG13) among its 17 goals.

TOWARDS THE HLPF: CIVIL SOCIETY AT THE PARTNERSHIP FORUM

The progress of the SDGs is monitored through a mechanism of consultations (Regional Forums) and voluntary national reviews (National Voluntary Reviews – VNRs) coordinated at the ECOSOC High Level Political Forum, the main UN platform dedicated to sustainable development at the global level that meets in plenary every July. Among the events that are part of this mechanism is the Partnership Forum, an event that aims to foster collaboration between governments, the private sector, non-profits and civil society to find new solutions for international development.

This year, recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic was at the centre of the Forum’s agenda, bringing out the different priorities between rich and low/middle income countries. Although economic and social recovery from COVID-19 is closely linked to the environmental and climate actions that should be taken based on the decisions made in recent years at the UN climate negotiations, there were few mentions of COP26 in Glasgow and climate action. Pakistan and Bangladesh recalled the results of COP26, referring to the urgency of finding funds for climate finance and the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts. Colombia stressed the importance of coalitions such as the Leaders’ Pledge for Nature and the Global Partnership for Oceans, important contributions to boost the ambition of key processes such as the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the construction of a global framework for biodiversity (one of the goals of the 2030 Agenda). Italy focused its intervention on the value of international cooperation, making a brief mention of the just transition, recommending a “global pact to promote the values of the United Nations and responsible business practices (…) aiming to achieve decent work for all by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and negative impacts on biodiversity”. The most comprehensive intervention came from Botswana, which launched an appeal to re-establish the value of international solidarity, avoid replicating unsustainable development practices adopted before the pandemic and relaunch financial support for development and climate action to ensure greater security and respect for human rights at the international level.

Once again, it was civil society that tried to bring to light the contradictions of a mechanism that is losing its democratic nature. The cross-sector collaborations promoted internationally by the Partnership Forum can lead to new solutions and sources of funding for development, but they must not replace the UN system of democratic governance. Emilia Reyez, Director for the organization Equitad de Genero, encapsulated the concerns of civil society in her speech, arguing that it is worrying that the UN is entrusting key aspects of international governance to private sector actors who are not imposed stringent controls over the social and environmental impact of their actions, while traditional mechanisms to protect human rights established after World War II are underfunded and thus weakened. This silent “reform” of the UN system risks perpetuating harmful patterns of cooperation by involving actors with undemocratic objectives, watering down the SDGs agenda, climate action and human rights protection.

Article by Chiara Soletti